Every lean organization recognizes the need for – and significance of – practicing Kaizen or continuous improvement. That Kaizen is integral to any lean initiative is clearly evidenced by the numerous references, discussions, and success stories in two highly recommended and revered books: “Lean Thinking: Banish Waste and Create Wealth in Your Corporation” by James P. Womack and Daniel T. Jones and “The Toyota Way” by Jeffrey Liker.

In this context, it’s not surprising when I hear managers say “We don’t do enough Kaizen here”, and is further accompanied by a sense of guilt that knowingly suggests they can’t be lean without it. When I ask them to clarify their statement, they often refer to their latest week-long Kaizen event that actually seemed more like an extended exercise in 5S.

In other more extreme cases, the value stream changes were so radical that they were actually practicing Kaikaku or radical improvement. Quite literally, the changes involved re-arranging machines and re-processing operations to improve flow and reduce inventories.

Over the course of my career, I have led several successful major plant transformations and turn-around efforts. Practicing Kaikaku is almost assured when, at some point, the discussion turns to “Pretend there is nothing in your plant” or, “If you could start from scratch”, “What would it look like?”

Although Kaizen is not intended to be as radical, I constantly hear the same concern from both small and medium-sized companies, “We simply don’t have the time or the resources to devote to a week-long workshop.” I always follow with, “Who said we need a week?

The problem with either of the scenarios above is that they have the tendency to be one time events by design. If, by definition, Kaizen is continual improvement, then “one time” events are clearly an exceptional form of the practice. Let’s take a few minutes to understand what Kaizen is.”

What is Kaizen?

The perception of Kaizen in the leadership and management ranks is based on a common misunderstanding of what Kaizen really is and, with so much information available on the topic, perhaps for good reason.

Many books have been written on the topic of lean and each presents their definition of Kaizen in kind. For example, “Lean for Dummies“, by Natalie J. Sayers and Bruce Williams, devotes an entire chapter to “Flowing in the Right Direction: Lean Projects and Kaizen”, and suggests:

… Kaizen is the how. Kaizen is the way you improve the value stream; it’s practiced through a continuing series of workshops and projects.

Further reading continues to expound on the definition of Kaizen, the rules for engagement, project selection, project methodology, as well as planning and conducting workshops.

As I reflect on my own experience, I recall a week-long process improvement initiative with one of Suzuki’s New Program Launch teams. They referred to this initiative as “Kaizen” and encouraged us to learn and pursue other process improvements using a similar strategy:

The objective of Kaizen is to continually improve, to pursue perfection with a focus on value added activities and the relentless elimination of waste.

The team consisted of personnel from a number of different departments and their entire time was to be devoted to this aggressive and rigorous process review and improvement activity. Personally, the experience was exhausting and the gains achieved certainly warranted the level of engagement demanded.

We were subsequently introduced to “Kaizen Blitzes” that were somehow less intense than a full workshop but seemed to be a more palatable approach.

The perception and resources required for week-long workshops are among the few primary reasons why many companies find it difficult to support Kaizen. Unfortunately, their only experience and exposure to Kaizen is often gained through these limited “workshop” or “blitz” experiences.

Indeed, entire books have been written on Kaizen alone that may be even more intimidating to the new and uninitiated lean practitioner. I prefer the description of Kaizen as presented in “Toyota Under Fire” by Jeffrey Liker and Timothy N. Ogden.

At Toyota, Kaizen isn’t a set of projects or special events. It’s the way people in the company think at the most fundamental level, harking back to Deming’s never-ending PDCA cycle.

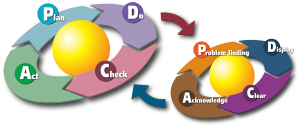

Although this definition is broader in scope, it identifies the PDCA cycle (Plan, Do, Check, Act) as the core premise of all continuous improvement initiatives and is consistent with the methodology purported by Mike Rother in his highly acclaimed book, “Toyota Kata” and also discussed in our post “Discover Toyota’s Best Practice” and referred by Wikipedia.

Two Types of Kaizen

Those of you who are familiar with Kaizen recognize that there are actually two types of Kaizen: Maintenance Kaizen and Improvement Kaizen.

Improvement Kaizen is “raising the bar” to the next level – improving processes to achieve new standards and higher levels of performance. The very nature of the improvement requires participation from multiple disciplines to discover and effect the changes necessary.

Maintenance Kaizen, as briefly described by Jeffrey Liker in “Toyota Under Fire“, is the reality of dealing with our daily unexpected crises (Murphy’s Law) – something most of us are exposed to in our workplaces and personal lives.

When we hear that employees at Toyota make daily improvements, it is likely in reference to Maintenance Kaizen and the Improvement Kata. In this context, we are all likely practicing Maintenance Kaizen on a daily basis too.

A recent experience

I can appreciate that some businesses work 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Of course supporting a business like that means you are operating on the same timeline.

Machine failures and quality concerns are all too common in manufacturing. To broaden the application and our thinking with regard to Kaizen specifically and Lean in general, this experience is based on a recent “IT” concern.

03:10 am – The client calls: “We’ve got a problem with our e-mail. It just stopped working. We need to get this information out to our client before 7:00 am this morning.”

03:30 am – I arrive to find a file in the Outbox anxiously waiting to find its way onto the internet. Any attempts made to free up space were denied, e-mails could not be deleted, archives couldn’t be executed. Any attempts to do anything relevant produced the following message:

03:47 am – The internet connection was fully functional, so I recommend sending the files directly from their 3rd party e-mail. This, by the way, was the contingency plan in the “unlikely” event of an internal server crash.

03:55 am – Files are sent and we begin looking for a solution to the problem at hand.

04:11 am – I find and run the program that should handle a scan and repair C:\Program Files\Common Files\System\MSMAPI\1033.

04:51 am – The scan is complete and I’m greeted with “Errors were found in this file. To repair these errors, click Repair.”

04:53 am – I click Details… and, as suspected, there were errors that prevented access to the file:

04:53 am – I return to the Repair screen and click repair.

05:11 am – A message appears on the screen and things suddenly got worse:

Fortunately, while the scan was running, we researched alternative data recovery options as well. We were forced to develop a solution, other than the one recommended by Microsoft, to successfully resolve the problem.

07:00 am – Problem resolved and the client is satisfied that all is well. Time to get ready for work!

Lessons Learned

The client was not performing regular archives resulting in a massive file at or near the limits of the software. Backups were few and seldom performed. The experience has now mandated the need for managed archiving and weekly backups.

How the file became corrupt is still a mystery. Although the risk of occurrence is unknown, just knowing that Microsoft developed a repair solution suggests that the event was at least expected to occur.

We conclude that the risk of recurrence is slim. There is little that can be done to assure the integrity of data as this is controlled by the file management capabilities of the software and the operating system itself.

Is this Kaizen?

The crisis was very real, required an immediate solution, and Murphy’s law prevailed on more than one occasion. Negligence regarding archives and backups was discovered and countermeasures were implemented accordingly.

It is very unlikely that we will be able to prevent a file from ever becoming corrupt, although appropriate countermeasures, such as backups, will at least minimize the risk. Our initial third-party e-mail solution negated the potential loss of any data.

I recognize that improvement initiatives are typically premised on a known process state whereby the amount of improvement can be measured. In the same context, a target condition that we aspire to achieve is also established.

Whether this was Kaizen is a matter of perspective. Whatever it is called, our mission is to maximize value for our customer by pursuing perfection through the relentless elimination of waste.

Kaizen Protocol

I don’t intend to minimize the rigors of Kaizen by the simplicity of the experience shared above. However, I contend that practicing Kaizen is not restricted to the realm of workshops or special events considering that, at the most fundamental level, improvement initiatives or Kaizen follow iterative cycles of the “Plan > Do > Check > Act” methodology.

As we continue to learn from our past experiences, the necessity for full workshops at the process level are eventually displaced by “spontaneous” improvement and problem solving on a reduced scale and at the “local” level.

It is not that companies are neglecting to do Kaizen, it is the failure to recognize that Kaizen is not an event, special project, or a workshop. Kaizen is the incremental improvements that we implement continually each and every day. Foregoing the formality of documenting every Kaizen activity does not negate the reality that it is being practiced.

Until Next Time – STAY lean!

Vergence Analytics

** A full Kaizen workshop requires substantial preparation and effort. Realizing this, some companies prefer to use simulations to teach Kaizen rather than risk disruptions to current processes or operations.

** Consultants bring a wealth of experience from a diverse range of businesses and industries. Consider hiring a consultant as a “resource on demand” to facilitate and practice Kaizen in your operation.

The reality of education is difficult within small businesses where roles and responsibilities do not exist. A sense of purpose is more important. Why am I here and what am I suppose to do. True leadership starts in the belief of the leadership in itself as to why it is there in the first place. Adding levels of ‘consultants’ and lean thinking boils down to this – time is money and waste of any time or resources deplete the effectiveness in any company. As companies grow from being Mr Rolls and Mr Royce to being Rolls Royce they lose the ability to really connect with the people who matter – the people who make things not just make things happen but actuality do make ‘things’. Staying connected and giving purpose to those who work and creating success through sales is what commerce is. True leadership is about vision and believing in that vision to create the opportunities to make it happen by giving it a purpose that their employees understand.

We couldn’t agree more. We highly recommend Patrick Lencioni’s “Three signs of a miserable job”, an excellent story that demonstrates that meaningful, measureable work performed by the person doing the work supercedes meaningless, immmeasureable work that anyone can do (anonymity).

True synergy occurs when goals of the company are aligned with personal employee goals to create a “win win” for both.

Thank you for sharing!